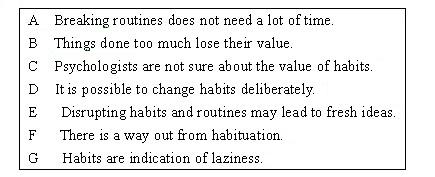

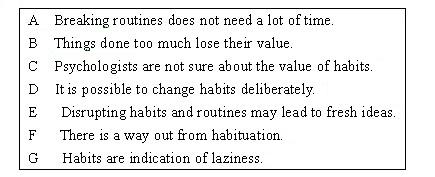

Part C You are going to read a passage about habits. From the list of headings A-G choose the best one to summarize each paragraph (33-38) of the passage. There is one extra heading that you do not need to use. Habits are bad only if you can’t handle them

We are endlessly told we’re creatures of habit. Indeed, this observation’s if it were origin is one of the most annoying habits of pop psychologists. The psychologist William James said long ago that life “is but a mass of habits … our dressing and undressing, our eating and drinking, our greetings and partings, our giving way for ladies to precede are things of a type so fixed by repetition as almost to be classed as reflex actions.” What pop psychology can’t decide, though, is whether this state of affairs is good or bad. Are habits, properly controlled, the key to happiness Or should we be doing all we can to escape habitual existence

We are endlessly told we’re creatures of habit. Indeed, this observation’s if it were origin is one of the most annoying habits of pop psychologists. The psychologist William James said long ago that life “is but a mass of habits … our dressing and undressing, our eating and drinking, our greetings and partings, our giving way for ladies to precede are things of a type so fixed by repetition as almost to be classed as reflex actions.” What pop psychology can’t decide, though, is whether this state of affairs is good or bad. Are habits, properly controlled, the key to happiness Or should we be doing all we can to escape habitual existence

This isn’t a question of good versus bad habits: we can agree, presumably, that the habit of eating lots of vegetables is preferable to that of drinking a three-litre bottle of White Lightning each night. Rather, it’s a disagreement about habituation itself. Since habit is so much more powerful than our conscious decision-, what are needed are deliberately chosen routines. No matter how hard you resolve to spend more time with your spouse, it’ll never work as well as developing the habit of a weekly night out of doing the hardest task first each morning.

This isn’t a question of good versus bad habits: we can agree, presumably, that the habit of eating lots of vegetables is preferable to that of drinking a three-litre bottle of White Lightning each night. Rather, it’s a disagreement about habituation itself. Since habit is so much more powerful than our conscious decision-, what are needed are deliberately chosen routines. No matter how hard you resolve to spend more time with your spouse, it’ll never work as well as developing the habit of a weekly night out of doing the hardest task first each morning.

Yet on the other hand, as we know all too well, habits hose their power precisely because they’re habitual. An expensive cappuccino, once in a while, is a life-enhancing pleasure; an expensive cappuccino every day soon becomes a boring routine. Even proven theutic techniques, such as keeping a diary, work better when done occasionally, not routinely.

Yet on the other hand, as we know all too well, habits hose their power precisely because they’re habitual. An expensive cappuccino, once in a while, is a life-enhancing pleasure; an expensive cappuccino every day soon becomes a boring routine. Even proven theutic techniques, such as keeping a diary, work better when done occasionally, not routinely.

I don’t have an answer to this dilemma. But there is one way to get the best of both words: develop habits and routines that are designed to disrupt your habits and routines, and keep things fresh. One obvious example is the “weekly review”, which time-management experts are always recommending: a habit, yes, but one that involves stepping out of the daily habitual stream to gain perspective. Or take Bill Cates’s famous annual “think week”, in which he holes up in the mountain with a stack of books and journals, to reflect on future paths of action. You don’t need a week in the mountains, though: an hour’s walk in the park each week might prove as beneficial.

I don’t have an answer to this dilemma. But there is one way to get the best of both words: develop habits and routines that are designed to disrupt your habits and routines, and keep things fresh. One obvious example is the “weekly review”, which time-management experts are always recommending: a habit, yes, but one that involves stepping out of the daily habitual stream to gain perspective. Or take Bill Cates’s famous annual “think week”, in which he holes up in the mountain with a stack of books and journals, to reflect on future paths of action. You don’t need a week in the mountains, though: an hour’s walk in the park each week might prove as beneficial.

A smaller-scale kind of routinised disruption is a method known as burst working, involving tiny, timed sprints of 5 to 10 minutes, with gaps in between. Each burst brings a microscopic but refreshing sense of newness, while each tiny deadline adds useful pressure, pring a descent into torpor. Each break, meanwhile, is a moment to breathe-a miniature “think week”, to step back, assess your direction, and stop the day sliding into forgetfulness.

A smaller-scale kind of routinised disruption is a method known as burst working, involving tiny, timed sprints of 5 to 10 minutes, with gaps in between. Each burst brings a microscopic but refreshing sense of newness, while each tiny deadline adds useful pressure, pring a descent into torpor. Each break, meanwhile, is a moment to breathe-a miniature “think week”, to step back, assess your direction, and stop the day sliding into forgetfulness.

All these techniques use the power of habituation to defeat the downsides of habituation. Like jujitsu(柔道), you’re turning the enemy’s strength against him; unlike jujitsu, we physically malcoordinated types can do it, too.

All these techniques use the power of habituation to defeat the downsides of habituation. Like jujitsu(柔道), you’re turning the enemy’s strength against him; unlike jujitsu, we physically malcoordinated types can do it, too.

()

Part C You are going to read a passage about habits. From the list of headings A-G choose the best one to summarize each paragraph (33-38) of the passage. There is one extra heading that you do not need to use. Habits are bad only if you can’t handle them

We are endlessly told we’re creatures of habit. Indeed, this observation’s if it were origin is one of the most annoying habits of pop psychologists. The psychologist William James said long ago that life “is but a mass of habits … our dressing and undressing, our eating and drinking, our greetings and partings, our giving way for ladies to precede are things of a type so fixed by repetition as almost to be classed as reflex actions.” What pop psychology can’t decide, though, is whether this state of affairs is good or bad. Are habits, properly controlled, the key to happiness Or should we be doing all we can to escape habitual existence

We are endlessly told we’re creatures of habit. Indeed, this observation’s if it were origin is one of the most annoying habits of pop psychologists. The psychologist William James said long ago that life “is but a mass of habits … our dressing and undressing, our eating and drinking, our greetings and partings, our giving way for ladies to precede are things of a type so fixed by repetition as almost to be classed as reflex actions.” What pop psychology can’t decide, though, is whether this state of affairs is good or bad. Are habits, properly controlled, the key to happiness Or should we be doing all we can to escape habitual existence

This isn’t a question of good versus bad habits: we can agree, presumably, that the habit of eating lots of vegetables is preferable to that of drinking a three-litre bottle of White Lightning each night. Rather, it’s a disagreement about habituation itself. Since habit is so much more powerful than our conscious decision-, what are needed are deliberately chosen routines. No matter how hard you resolve to spend more time with your spouse, it’ll never work as well as developing the habit of a weekly night out of doing the hardest task first each morning.

This isn’t a question of good versus bad habits: we can agree, presumably, that the habit of eating lots of vegetables is preferable to that of drinking a three-litre bottle of White Lightning each night. Rather, it’s a disagreement about habituation itself. Since habit is so much more powerful than our conscious decision-, what are needed are deliberately chosen routines. No matter how hard you resolve to spend more time with your spouse, it’ll never work as well as developing the habit of a weekly night out of doing the hardest task first each morning.

Yet on the other hand, as we know all too well, habits hose their power precisely because they’re habitual. An expensive cappuccino, once in a while, is a life-enhancing pleasure; an expensive cappuccino every day soon becomes a boring routine. Even proven theutic techniques, such as keeping a diary, work better when done occasionally, not routinely.

Yet on the other hand, as we know all too well, habits hose their power precisely because they’re habitual. An expensive cappuccino, once in a while, is a life-enhancing pleasure; an expensive cappuccino every day soon becomes a boring routine. Even proven theutic techniques, such as keeping a diary, work better when done occasionally, not routinely.

I don’t have an answer to this dilemma. But there is one way to get the best of both words: develop habits and routines that are designed to disrupt your habits and routines, and keep things fresh. One obvious example is the “weekly review”, which time-management experts are always recommending: a habit, yes, but one that involves stepping out of the daily habitual stream to gain perspective. Or take Bill Cates’s famous annual “think week”, in which he holes up in the mountain with a stack of books and journals, to reflect on future paths of action. You don’t need a week in the mountains, though: an hour’s walk in the park each week might prove as beneficial.

I don’t have an answer to this dilemma. But there is one way to get the best of both words: develop habits and routines that are designed to disrupt your habits and routines, and keep things fresh. One obvious example is the “weekly review”, which time-management experts are always recommending: a habit, yes, but one that involves stepping out of the daily habitual stream to gain perspective. Or take Bill Cates’s famous annual “think week”, in which he holes up in the mountain with a stack of books and journals, to reflect on future paths of action. You don’t need a week in the mountains, though: an hour’s walk in the park each week might prove as beneficial.

A smaller-scale kind of routinised disruption is a method known as burst working, involving tiny, timed sprints of 5 to 10 minutes, with gaps in between. Each burst brings a microscopic but refreshing sense of newness, while each tiny deadline adds useful pressure, pring a descent into torpor. Each break, meanwhile, is a moment to breathe-a miniature “think week”, to step back, assess your direction, and stop the day sliding into forgetfulness.

A smaller-scale kind of routinised disruption is a method known as burst working, involving tiny, timed sprints of 5 to 10 minutes, with gaps in between. Each burst brings a microscopic but refreshing sense of newness, while each tiny deadline adds useful pressure, pring a descent into torpor. Each break, meanwhile, is a moment to breathe-a miniature “think week”, to step back, assess your direction, and stop the day sliding into forgetfulness.

All these techniques use the power of habituation to defeat the downsides of habituation. Like jujitsu(柔道), you’re turning the enemy’s strength against him; unlike jujitsu, we physically malcoordinated types can do it, too.

All these techniques use the power of habituation to defeat the downsides of habituation. Like jujitsu(柔道), you’re turning the enemy’s strength against him; unlike jujitsu, we physically malcoordinated types can do it, too.