下载APP

【单选题】

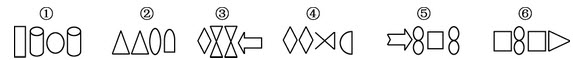

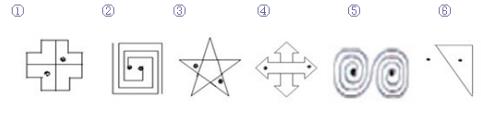

A.①③⑥,②④⑤

B.①②⑤,③④⑥

C.①③④,②⑤⑥

D.①④⑤,②③⑥

A.

把下面的六个图形分为两类,使每一类图形都有各自的共同特征或规律,

B.

分类正确的一项是()

C.

举报

参考答案:

参考解析:

刷刷题刷刷变学霸

举一反三

【单选题】According to Schwartz, what can help people know more about climate change ?() A.Taking a course on phenology. B.Knowledge of life cycle events of plants and animals. C.Efforts of ecologists to learn ...

A.

Understanding how nature reacts to climate (气候) change will require checking key life cycle events--flowering, the appearance of leaves, the first frog calls of the spring--all around the world. But ecologists (生态学家) can’t be everywhere, so they’re turning to non-scientists, sometimes called citizen scientists, for help.

B.

A group of scientists and educators set up an organization last year called the National Phenology Network. "Phenology" is what scientists call the study of the timing of events in nature.

C.

One of the group’s first efforts is to ask scientists and non-scientists to collect information about plant flowering and leafing every year. The program, called Project BudBurst, collects life cycle information on a variety of common plants from across the United States. People taking part in the project record their information on the Project BudBurst website.

D.

"People don’t have to be scientists--they just have to look around and see what’s in their neighbourhood," says Jennifer Schwartz, a scientist with the project. "As we collect this information, we’ll be able to know about the changes of plants and animals as the climate changes. "

E.

Not only that, the information also helps scientists learn about how these changes will have an effect on people, Scientists examining lilac (丁香花) flowering in western United States reported that in years when lilacs flowered early--before May 20th-wildfires later in the summer and fall were likely to be larger and more serious. Lilac flowering, then, could serve as an alarm bell.

F.

"The best way for us to increase our knowledge of how plants and animals are reacting to climate change is to increase the count of information we have," Schwartz says. "That’s why we need citizen scientists to get as much information from as many places on as many plants and anireals over as long a time period as we can. \

【单选题】有些被宣称为“清热下火”的凉茶,其实连茶的远亲都算不上,它们不是普通的“茶叶”,只是含些中草药提取液。从现代医学角度看,人体的许多症状跟中医所说的“热”,“火”类似,而这些症状,有许多是会自然减退的,不管喝凉茶还是白水,一段时间后都会减轻。另一方面,在理论上完全可能有中草药的某些成分正好对某些症状有效,所以不少人喝了凉茶,觉得清了“热”,下了“火”,这并不奇怪。但是,这样一种“有效”却符合大众的思...

A.

乱喝凉茶可能会对健康不理

B.

很多消费者并不了解凉茶的实质

C.

某些凉茶“清热下火”的功能值得怀疑

D.

凉茶中真正发挥功效的是中草药成分

【单选题】能够从上述资抖中推出的是() A.2009年上半年,全国原油进口量高于原油产量 B.2009年上半年,全国汽油产量同比增长事高于柴油 C.2009年一季度,全国成品油表观消费量高于二季度 D.2009年-上丰年,全国天然气产量同比增长l4%

A.

二、根据以下资料,回答126~130题 2010年上半年,全国原油产量为9848万吨,同比增长5.3%,上年同期为下降1%。进口原油11797万吨(海关统计),增长30.2%。原油加工量20586万吨,增长17.9%,增速同比加快16.4个百分点。成品油产量中,汽油产量增长6%,增速同比减缓7.9个百分点;柴油产量增长28.1%,增速同比加快15.8个百分点。 据行业统计,2010年上半年成品油表观消费量10963万吨,同比增长12.5%。其中,一、二季度分别增长16.3%和9.2%。 201O年6月份,布伦特原油平均价格为75.28美元/桶,比上月回落1.75美元/桶,同比上涨10.4%。结合国际市场油价变化情况,国家于6月1日将汽油、柴油批发价格分别下调230元/吨和220元/吨。 2010年上半年,全国天然气产量459亿立方米,同比增长10.8%,增速同比加快3.2个百分点。国家于6月1日将国产陆上天然气出厂基准价格上调了230元/千立方米。 2010年1-5月,石油石化行业实现利润1645亿元,同比增长76.4%,上年同期为下降35.4%。其中,石油天然气开采业利润1319亿元,同比增长1.67倍,上年同期为下降75.8%,炼油行业利润326亿元,同比下降25.7%,上年同期为增长1.8倍。

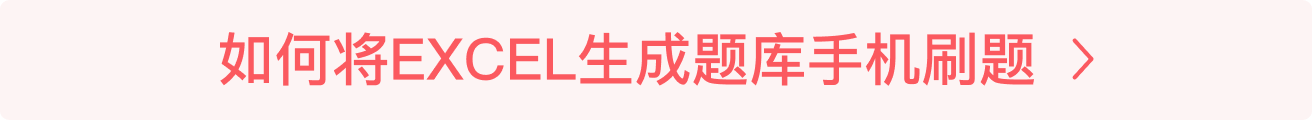

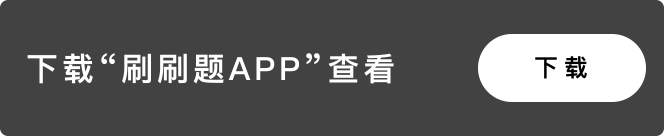

【单选题】A.①②⑥;③④⑤ B.①②③;④⑤⑥ C.①④⑤;②③⑥ D.①④⑥;②③⑤

A.

把下面的六个图形分为两类,使每一类图形都有各自的共同特征或规律,分类正确的一项是()

B.

【单选题】信用卡从根本上改变了我们的花钱方式,当我们用现金买东西时,购买行为就涉及到实际的损失--------我们的钱包变空了,然而,信用卡却把交易行为()化了,这样我们实际上就不容易感觉到花钱的消极面了,脑成像实验表明,刷卡真的会降低脑岛的活动水平,而脑岛是与消极情绪有关的脑区。信用卡的实质就是()我们,让我们感觉不到付账的痛苦。依次填入括号部分最恰当的一项是()

A.

合理;麻痹

B.

抽象;麻醉

C.

简单;迷惑

D.

概念;蒙蔽

【单选题】诗人从生活和大自然捕捉灵感,将语言剪裁成诗;知音的理解和回响,可以使诗的意象和隐藏其中的思想感情浮现出来,天地一沙鸥,海上生明月,悠然见南山,经由后人的吟诵品味,其意向更为深化:巴山夜雨,易水悲歌,汉关秦月,江山风光人物诗文相互烘托,转化为跨时空的文化符号,丰富了文学的内容,影响一代代人的精神面貌。这段文字的关键词是()

A.

诗;知音;意象

B.

自然;灵感;文化

C.

生活;感情;品味

D.

文学;符号;精神

【单选题】(38)处应填()。 A.support B.attack C.advance D.escape

A.

I’m told that during an international game of chess (国际象棋), many beautiful moves could bc made on a chessboard. In a decisive (36) in which he was evenly matched with a Russian master (37) , Marshall found his queen under serious attack. There were several ways of (38) , and since the queen is the most (39) piece, spectators (观众) thought Marshall would naturally move his queen to (40) .

B.

Deep in thought, Marshall used all his time to consider the (41) . He picked up his queen, paused, and placed it down on the most (42) square of all--a square from which the queen could be (43) by any one of three enemy pieces.

C.

Marshall had sacrificed (牺牲) his queen--an unthinkable move. Everyone else was (44) .

D.

Then the Russian, and the (45) , realized that Marshall had actually made a (46) move. It was clear that no matter how the (47) was taken, the Russian would soon be in a (48) position. Seeing this, the Russian admitted his defeat.

E.

When spectators recovered from the (49) of Marshall’s dating, they showered the chessboard with money. Marshall had achieved (50) in a very unusual and dating fashion--he had (51) by sacrificing the queen.

F.

To me, it’s not (52) that he won. What counts is that Marshall had broken with standard (53) to make such a move. He had looked (54) the usual patterns of play and had been willing to consider an imaginative risk on the basis of his judgment and his judgment alone. No matter how the game (55) , Marshall was the winner.

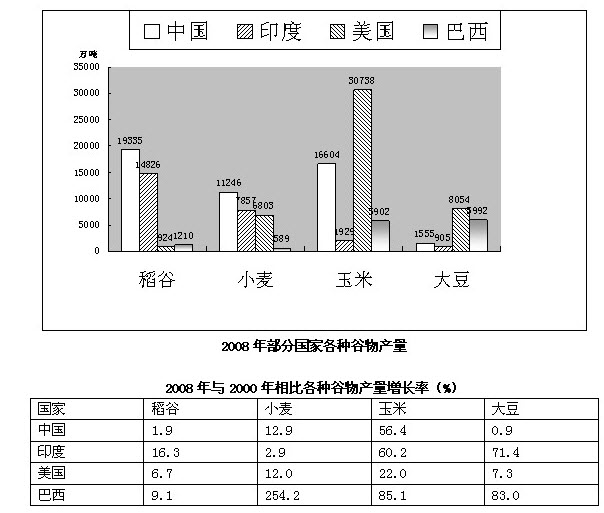

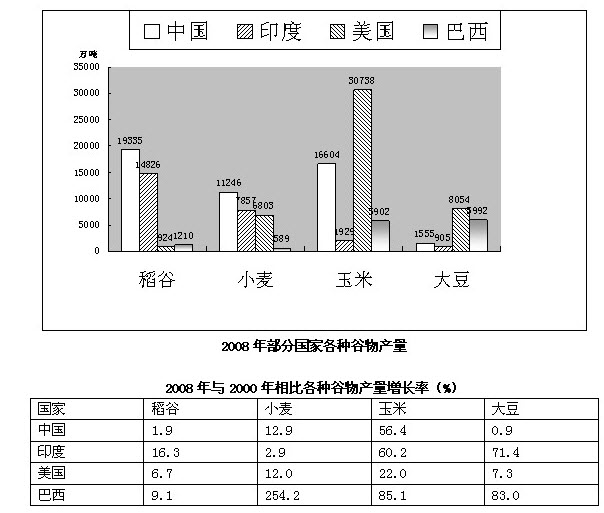

【单选题】2000年,表中所列四国玉米的最高产量约是最低产量的多少倍() A.11 B.16 C.21 D.26

A.

一、根据以下资料,回答121~125题。 2008年世界稻谷总产量68501.3万吨,比2000年增长14.3%;小麦总产量68994.6万吨,比2000年增长17.8%;玉米总产量82271.0万吨,比2000年增长39.1%;大豆总产量23095.3万吨,比2000年增长43.2%。

B.

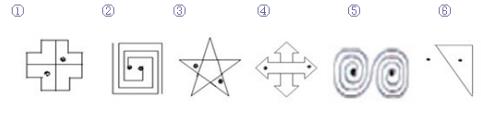

【单选题】A.①③④,②⑤⑥ B.①⑤⑥,②③④ C.①②⑥,③④⑤ D.①②④,③⑤⑥

A.

以下86-90题,每个题目包含六个图形,请把此六个图形分为两类,使得每一类图形都有各自的共同特征或规律。()

B.